Reel Artists Film Festival brings artist Kehinde Wiley and his soaring collaboration with Givenchy to Toronto

See our RAFF opening night gallery »

Did you know that Toronto is home to the world’s only art on film festival? Or that it is in its 11th year? Probably not. For the past few years, the Reel Artists Film Festival has blown us away with its A-list roster of films, talent and frankly, how underrated it is. This year, RAFF upped the ante yet again by premiering An Economy of Grace, a film about artist Kehinde Wiley and his unique brand of hood-meets-highbrow in pieces that portray African Americans in heroic poses.

At Wednesday night’s opening, the who’s who of Toronto’s art scene fêted the film, hobnobbing with the artist and taking in an onstage Q&A with him and Zoomer editor-in-chief Suzanne Boyd, which focused on the sociological impact his pieces have on his subjects as well as his work with Givenchy.

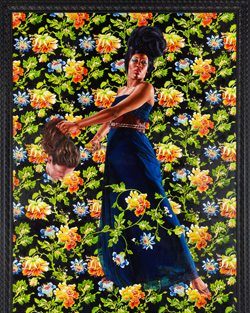

An Economy of Grace follows Wiley as he creates his first women-only painting series, casting them on the street in Harlem, dressing them in couture gowns and transforming them into large-scale re-imaginations of classic works of art. It also documents the artist’s collaboration with Givenchy creative director Riccardo Tisci, who created the dresses exclusively for the paintings. “When I thought about the absolute favourite of favourites or what stood for the best of haute couture, it was Givenchy,” said Wiley of the partnership. As current fashion plays so comfortably in the arena of high low, Wiley’s work touches on how once impossible that kind of combination would have been. In the days of great master portraiture (Wiley’s work often draws directly from Titian, Ingres, John Singer Sargent and Napoleon painter Jacques Louis David), subjects would have been those with money, wealth and social stature. They certainly would never have been of colour, something Wiley’s work flips on its head.

Read our interview with Kehinde Wiley »

RAFF keeps the fashion momentum going through the weekend with a lecture by Prada curator and art historian Germano Celant, following a screening of his When Attitudes Become Form tomorrow at 1PM. For more information about the festival, visit iso.canadianart.com.

How did the collaboration with Givenchy come about?

“When I thought about the absolute, like, favourite of favourites, or like what stood for the best of haute couture, it was Givenchy. Part of it is just the legacy of the organization. For this project I wanted to do an absolute glam for these girls.”

Tell us more about the project

“It’s all young black girls from underserved communities within New York and the idea was to do this sort of transformation scene; you’d go into art history and you’d recreate these fabulous one of a kind gowns and then I’d make paintings of those girls who were like randomly cast from the streets. Riccardo [Tisci] was totally up to it. We would meet at the Louvre in Paris and we’d walk through on the days when the museum was closed. Imagine a private audience in the Louvre? So it’s just yours. You’re standing in front of the Mona Lisa, and you’re chatting it up with Riccardo about how we’re going to make a beautiful gown for these paintings. Oh, it was insane. Insane. It was a dream project.”

What’s your favourite painting from this series?

“I would say the Holofernes portrait is really nice. That’s the decapitation painting, and it’s just really dramatic and sort of ballsy.”

How do you um how do you chose your reference points?

“In the past it’s always been about ego. You know, all that chest beating and flossing. So much of the history of art is about the history of powerful men who’ve practiced their entire lives for this role. This is, this is proof to the rest of the world about how powerful and how clever and how full of agency they are. And painting has this beautiful and perverse history, I mean, it’s both at the service of this adulation of the ego, but it’s also something that’s heartbreakingly beautiful. I mean, something that takes a lot of time, and effort and talent to pull off.

In my own work, I try to concentrate on both critiquing some of the sillier bits of it but also like really celebrating how amazing it is, that you can take that power and turn it towards people who are ignored. Who in their wildest dreams would imagine they would be walking to the subway line just trying to get to work and the next moment there’s this chance interaction, with this guy. And now they’re hanging in the great museums of the world. It’s um that kind of, sort of play with circumstances.”

How does your appreciation for art history or history in general affect your work?

“Well one of hallmarks of post modernity has to do with a level of irony and a level of remove that doesn’t allow you the viewer or you the artist to participate in society or in real life without this wink, like ‘I’m not really part of this’ And you know, my work is actually like sort of painstakingly sincere. As opposed to wearing the ball gown with sneakers, I’m wearing the ball gown with the heels, right? I’m allowing it to be a moment of unadulterated celebration of an individual. The question then becomes, how does this relate to the broader evolution of culture, how does this relate to modern art in, in, in the 21st century? How do people create painting that matters today? And for me, it’s always been about inclusion. That simple act of saying yes to chaos.”

And those circumstances obviously are very different across the globe

“You know, I threw myself, years ago, off of my comfort level and started doing this project internationally. Been to Sri Lanka and Sao Paulo, India, Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, and Beijing, and each place reveals a completely different set of realities and strategies. Like how do you walk up to complete strangers in the streets of the Congo, you know what does that look like? I mean what do people dress like when they get the invitation to be in a painting. And are they trying to please me as a painter or do they even know what’s going on? Are they just confused, are they just there for the money? Like all of these questions and all of these confusing aspects about it are what gives it texture and what makes it worthwhile.”

Do you ever ask them?

“Yeah, sure. But I think ultimately what you’re going to get is so many different ways of engaging this thing, like in America it’s so different from it is in other parts of the world because people have this sort of ‘Just add water’ celebrity mentality, like ‘Of course, you’ve found me… This is my moment.’ Whereas in other places, I think there’s just a little bit more of this type of innocence you get. Either overwhelming curiosity or just sort of being paralyzed by how weird this whole thing is. Or conversely, being in parts of the world where that much attention and those cameras and those lights are associated with state power and the police. And so people are running and taking to the hills because they don’t know what the f*ck is going on.”

An Economy of Grace screens again tonight, February 21, 2014 at 7PM. For more information about the festival, visit iso.canadianart.com.